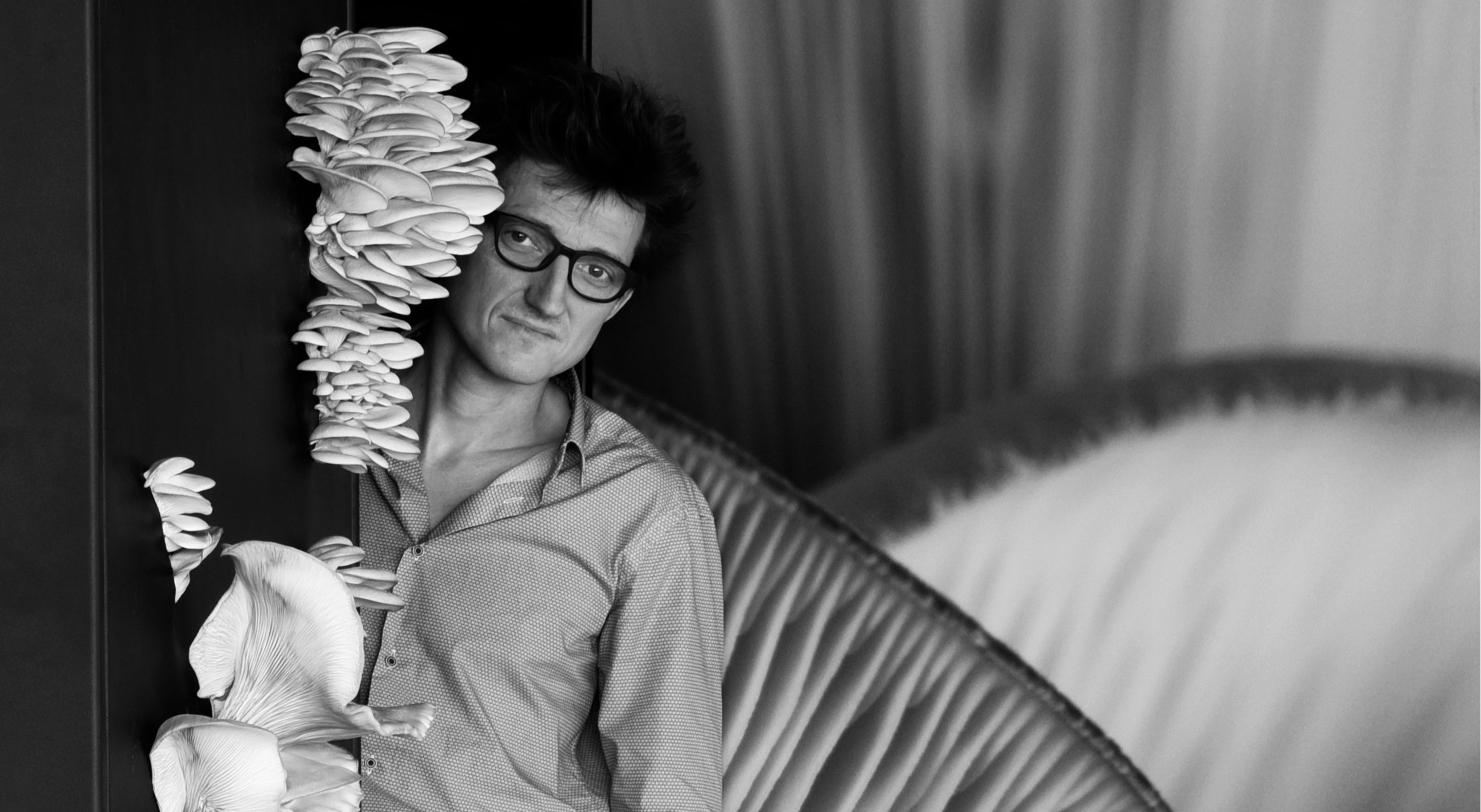

Germain Bourré, sensitive nature

Published on 29 May 2020

Being a culinary designer is a profession full of promises: working with fruit and vegetables, and, indeed, everything produced by the land, holds a mirror up to how we use the world...

“Designing’s about questioning the artistry as much as the purpose”, says Germain Bourré with a smile. For him, picking up a pencil is the very last stage in the entire creative process.

“I’m totally incapable of coming up with a shape just for the sake of it, if there’s no meaning behind it”

At the last edition of Maison&Objet, Germain Bourré’s exhibit, which was entitled “Back home from market”, featured refrigerated and ventilated transparent domes showcasing cheese, succulent vegetables and fresh fish. His anti-fridge encouraged onlookers to become fully conscious consumers by actively seeing and respecting food, sharing the same message in terms of both its content and form. The transparent domes took centre stage on the kitchen worktop in Ramy Fischler’s apartment/installation, “Design, and... Action!”, which explored future lifestyle trends.

Germain Bourré has always been an explorer, thinker, deliberator, and his interest in culinary design began at a very young age. As he completed his studies at the College of Art and Design in Reims (ESAD - Ecole supérieur d’art et de design), from which he graduated in the year 2000, his lecturers Marc Bretillot and Stéphane Bureaux were just starting to lay the foundations of this highly subtle and delicate field. Germain Bourré could already sense it was a field that offered endless possibilities. He began working with chefs, such as Arnaud Lallement and Jean-Pierre Vigato. In the kitchen, his role as a designer involved helping the chef tell his story on the plate, inventing presentation ware and crafting the story that would be presented to guests in the restaurant, accompanying each dish. In 2015, the ESAD-Reims invited him to head up its new Culinary Design masters degree programme.

From determining how a finished dish will look to designing the plate on which it will be served, or dreaming up a counter space or a point of sale or even creating packaging, culinary design is a multi-faceted affair and one that Germain Bourré refuses to pigeon hole into just one box. In his early days, he spent five years working alongside Jean-Marie Massaud trying his hand at designing perfume bottles for Lancôme and stands for football stadiums. He loves the fact that his work is so varied, as in his eyes, “design must embrace a number of different worlds in order to cross-fertilise expertise”. He’s equally open-minded when its comes to raw materials: after all, a carrot or leek represent a working base in exactly the same way as wood, stone or plastic. He’s an ardent believer that everything that comes from the earth must be treated with the utmost respect. He sees it as the designer’s role to challenge the stakes surrounding everything he does. He can set his sights on changing the world. In recent times, those stakes have focused on consumer sobriety and reassessing our basic needs.

In 2005, Germain Bourré set up his own agency, now called Germ Studio. “Germ Studio acts as that fly in the ointment that forces us to slow down and get back to nature”, he says. “Nature has always been so much better at everything than us. It’s able to regenerate. It’s out there for the taking.” After spending time in lockdown, the designer’s mind is positively whirring and teeming with unanswered questions. “What’s the point in constantly producing more if we don’t make any basic changes to the way we live our lives? What’s the point of replacing the petrol in our cars with bio-fuel if we still continue using them just as much? The crops will end up depleting the soil. The same goes for replacing single-use bags with bags made from maize starch but that nonetheless contain oil. We need to change our habits rather than simply substituting one raw material for another.”

He’s recently set up a think tank that brings together scientists, farmers, philosophers, doctors and engineers, going by the name of Sols (“Ground” in French). The self-same ground from which we extract oil, stone and the vegetables we eat. The very materials whose use the designer is keen to challenge. What are we going to do with them, and how? Design is right at the heart of the debate.